Be aware of __pycache__ poisoning attacks

November 14, 2023

-> g

Motivation #

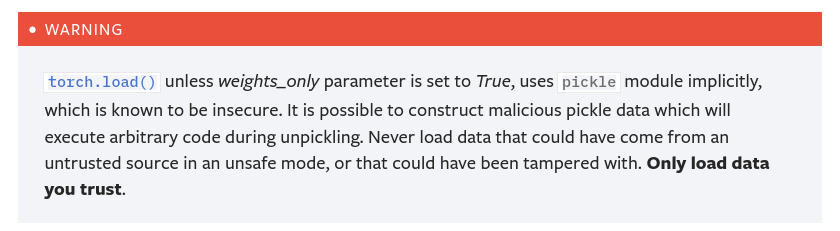

If you have used any popular deep learning framework (like PyTorch, TensorFlow, etc.) to build a simple hello world classifier from a dataset you downloaded from Kaggle, HuggingFace, or whatever corner of the web; you probably already know what a pickle file is, and probaby you might also be aware of the big red warning boxes decorating its reputation.

There are a lot of good articles showcasing how pickle files can be weaponized to execute malicious code into your system and execute malware immediately after you load a pickle file. The risks and issues of serialization formats, widely used in the machine learning ecosystem, make sharing pre-trained models and training datasets dangerous.

Considering the valuable hardware resources a company might utilize to train and deploy extensive machine-learning models, it is logical to assume that cryptocurrency-mining gangs and other malicious actors might want to target your computer clusters for malicious gains. Microsoft has discovered large-scale attacks targeting Kuberflow instances in the past in an attempt to install cryptocurrency-mining malware and use those powerful systems for malicious usage.

There are discussions and workarounds around pickle’s risks, but pickle files are not going to disappear anytime soon. Findings of an analysis from Splunk indicate that a vast portion of HuggingFace’s models consist of pickle-serialized code. That is why HuggingFace has deployed a pickle scanner to combat malicious pickle files from being deployed and harming the ecosystem. Not only that, but HuggingFace has also proposed and experimented with a new, safer alternative serialization format called safetensors.

All those conversations and efforts to implement more robust and secure practices in the machine-learning ecosystem inspired me to research new threats that might lie under our beds without our knowledge. This lead me to a not so widely known issue of the python’s caching system.

PEP 3147 - PYC Repository Directories #

Every python developer is familiar in some extent with python’s cache files usually found under each module’s __pycache__ folder. The first time a module is imported to a python program, CPython compiles its source code and caches its byte code under module/__pycache__/ folder. In that way, python’s importing system does not need to compile subsequent imports of a module multiple times.

The modern __pycache__ folder was first introduced in

PEP 3147. The enhanced proposal’s rationale for its introduction was to allow different installed python versions to load a module from the same directory and organize its cached compiled versions into a single directory. Suppose you import a module with two different python major versions. In that case, you will notice that under the __pycache__ folder, you get two compiled versions of the module, each corresponding to a different python major version.

For example if you try to import a module named my_module with python 3.6 and python 3.7 you will get the following tree:

my_module/

my_module.py

__pycache__/

my_module.cpython-36.pyc

my_module.cpython-37.pyc

In the same enhanced proposal, you can find the exact mechanism the import system uses to locate, verify, recompile, and load a cached version of the module from the cache.

Figure 1: Illustration describing how modules are loaded. Source: https://peps.python.org/pep-3147/#flow-chart

In Figure 1, you can see how the import system locates compiled cached files. But, once a compiled cached file is found, the import system needs to account for a few cases to ensure the cached version is recent and valid before loading it. Otherwise, the import system must recompile the source files to refresh the cache. A brief understanding of the binary format of a compiled python file (.pyc) is needed to understand how the import system handles these cases.

PYC File format #

The PYC file format is a straightforward format comprising a metadata header followed by a marshaled code object that encapsulates the byte code of a module. Therefore, the PYC format is a serialization file format, much like the pickle serialization format.

A simple python script that parses and shows the disassembled compiled byte code of a python script named my_file.py:

import dis

import marshal

import importlib

cached_filepath = importlib.util.cache_from_source('my_file.py')

cached_file_byte_contents = open(cached_filepath, 'rb').read()

# This works for python versions >= 3.8, for older versions the

# metadata header might be smaller.

marshaled_code_object = cached_file_byte_contents[16:]

code_object = marshal.loads(marshaled_code_object)

dis.dis(code_object)

Output:

2 0 LOAD_NAME 0 (print)

2 LOAD_CONST 0 ('This is my file :)')

4 CALL_FUNCTION 1

6 POP_TOP

3 8 LOAD_NAME 0 (print)

10 LOAD_CONST 1 ('My file: ')

12 LOAD_NAME 1 (__file__)

14 FORMAT_VALUE 0

16 BUILD_STRING 2

18 CALL_FUNCTION 1

20 POP_TOP

22 LOAD_CONST 2 (None)

24 RETURN_VALUE

The original source code of my_file.py:

print("This is my file :)")

print(f"My file: {__file__}")

This simple python script demonstrates the simplicity of the PYC file format (for more details on code objects you can read

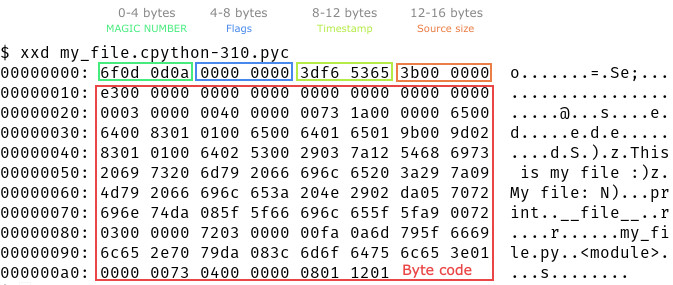

this nice article). However, the metadata header is the most useful for the import system for deciding whether to load or invalidate a cached compiled file. The metadata header has been and probably will be subject to future changes. But the contents of a typical metadata header of a PYC file in python versions >= 3.8 contains the following data:

- [0-4 bytes]: A magic number that changes with each modification to python’s byte code instruction set. In practice, this changes with each python major release.

- [4-8 bytes]: A dword flag that indicates to the import system how to validate the pyc file. Supported values 0, 1, and 3.

- [8-12 bytes]: The last modification timestamp or the first half of the siphash13 hash of the source file.

- [12-16 bytes]: The size of the source file if the flag is 0 or otherwise the second half of the siphash13 hash of the source file

Below you can see the actual source code used to create a pyc file:

def _pack_uint32(x):

"""Convert a 32-bit integer to little-endian."""

return (int(x) & 0xFFFFFFFF).to_bytes(4, 'little')

def _code_to_timestamp_pyc(code, mtime=0, source_size=0):

"Produce the data for a timestamp-based pyc."

data = bytearray(MAGIC_NUMBER)

data.extend(_pack_uint32(0))

data.extend(_pack_uint32(mtime))

data.extend(_pack_uint32(source_size))

data.extend(marshal.dumps(code))

return data

def _code_to_hash_pyc(code, source_hash, checked=True):

"Produce the data for a hash-based pyc."

data = bytearray(MAGIC_NUMBER)

flags = 0b1 | checked << 1

data.extend(_pack_uint32(flags))

assert len(source_hash) == 8

data.extend(source_hash)

data.extend(marshal.dumps(code))

return data

By default, pyc files are timestamp checked. In that case, each pyc file contains in its metadata header the last-modification timestamp and the source file size in bytes. Python compares the timestamp and the total source size embedded in the pyc metadata header with the source file. If they match, the cached compiled file can be safely loaded. Otherwise, the cached file is invalidated, and the source file is recompiled.

Figure 2: Illustration of the raw binary contents of my_file.py.

__pycache__ poisoning

#

What is most interesting about validating pyc files is that there is no verification on the byte code. This is expected because verifying the byte code of a cache file does not make sense. In addition, it is a challenging task to implement. As a result, it is possible to construct a pyc file with a perfectly valid metadata header and any arbitrary payload inside it.

This issue can be exploited to hide backdoored malicious code that can evade detection and as a security vulnerability in case you have misconfigured the file permissions on pycache directories, as demonstrated here.

It has come to notice that hiding malware in pyc files is a new trend. Just recently, ReversingLabs discovered a package named “fshec2” on the PyPI repository, which had malware code hidden in a pyc file. This incident highlights the fact that pyc files can be used as a good hiding place for malware.

It is possible to be even more sneaky by hiding backdoors in pyc files. Infecting pyc files that are located under the __pycache__ directory of a module can be an even better place to hide backdoors. Once a module is imported, the hidden backdoor can be activated immediately. The inspection of source files corresponding to pyc files can be misleading. Most developers are used to seeing cached compiled files under __pycache__ directories. They keep appearing on their systems again and again!

It’s worth noting that Python’s importing system automatically loads by default .pyc files located under the __pycache__ directory. To prevent Python from generating compiled byte code, you can set the PYTHONDONTWRITEBYTECODE environment variable to a non-empty value or use the -B switch flag. However, to prevent Python from loading cached .pyc files from an untrusted module, you would need to set the PYTHONPYCACHEPREFIX environment variable. But this environment variable is a relatively new feature (see

here) and is only supported on python versions >= 3.8. Not only that, but nothing prevents a program from modifying the

sys.pycache_prefix variable directly from a source file, by this way circumventing the PYTHONPYCACHEPREFIX mitigation. As a result, it seems that the most efficient and effective way to protect yourself from loading untrusted .pyc files from the __pycache__ directory is to wipe (use

pyclean for example) them prior to executing any code.

Figure 3: Illustration of the best way to protect yourself from untrusted pyc files is to clean them. Source: reddit

If you want to modify a cached pyc file without messing around with timestamps or hashing source files, the easiest way is to exploit the metadata header flags of the pyc file. The modern metadata header was introduced in

PEP-552 with the aim of better supporting reproducible builds. This proposal extended the metadata header to support source file hashes as well. Additionally, it introduced a check_source flag in the flags field of the metadata header. If this flag is not set, python will not validate the contents of the metadata header at all. The purpose of the check_source is to allow third-party programs to decide whether the contents of a cache file should be refreshed.

To corrupt a cached pyc file, one only needs to activate hash-based validation while disabling the check_source flag and then replace the file’s content. The compileall utility can be used as a quick and simple way to accomplish this task.

python3 -m compileall --invalidation-mode unchecked-hash my_malicious_file.py && mv __pycache__/my_malicious_file.cpython-310.pyc __pycache__/my_file.cpython-310.pyc;

If we run now the disassembling script we wrote before the output will be:

1 0 LOAD_NAME 0 (print)

2 LOAD_CONST 0 ('Malicious code is loaded instead!')

4 CALL_FUNCTION 1

6 POP_TOP

8 LOAD_CONST 1 (None)

10 RETURN_VALUE

PEP-552 introduced the --check-hash-based-pycs flag in Python to control loading behavior. When --check-hash-based-pycs always is used, the hash in the metadata header is always checked. As a result, if the hash in the metadata header is invalid, the cached files that are poisoned will not be loaded. To poison a pyc file effectively, a valid metadata header is also needed.

The end #

Next time you download any untrusted PyTorch/TensorFlow/Keras model, ensure to delete all pyc files before executing any code from Github, HuggingFace, or any other source :)